Climate change and Estonia: what we should know and do

In light of the recently published report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), researchers of the University of Tartu Centre for Sustainable Development point out eight key facts and nine activities connected with Estonia and climate change. These are for general information to the public and for inspiration to the new coalition government. Energy, which has received much attention, has been deliberately left out, even though greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector account for about half of Estonia’s annual emissions.

The IPCC’s synthesis report of the sixth assessment report unequivocally states that little time is left for humanity to halt climate change and prevent its worst consequences. The goal set in the Paris Agreement, which entered into force in 2016, to limit global warming to 1.5°C by the end of this century is slipping away. The measures introduced to limit greenhouse gas emissions so far have had an impact. Still, too few of them have been implemented and too slowly. A superficial attitude to climate change and its impacts – as if it all were far from us in time and space – is dangerous. The choices we make today will affect us for hundreds and thousands of years.

Eight facts about Estonia and climate change

1. Climate change has already arrived in Estonia

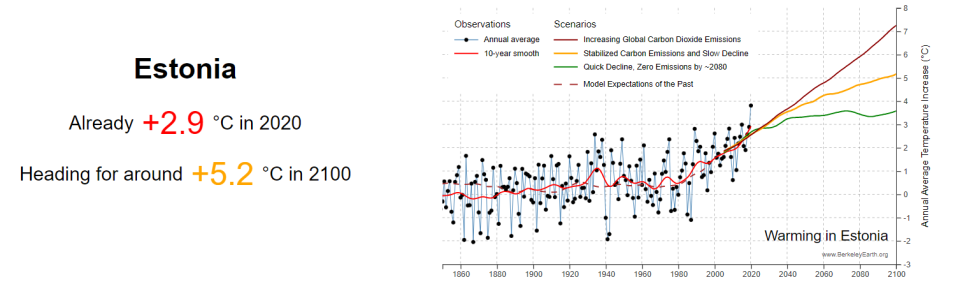

In Estonia, too, heatwaves are getting stronger, droughts longer and downpours more dangerous year by year (see figure). The synthesis report emphasises that we not only need to address the mitigation of climate change but already have to actively adapt to climate change in all areas.

Figure 1. Climate warming in Estonia since the mid-19th century and forecast by the end of this century. Source: berkeleyearth.org.

2. The world is heading for a three-degree rise in global temperatures by the end of the century, with human activity as its major cause

We now know that climate change is anthropogenic, but we also know how extensive it will become and how it will affect nature and humanity. Climate projections and our ability to anticipate the impacts of climate change are better than ever. We are heading for a three-degree warming, which will turn many densely populated parts of the planet uninhabitable or unfit for human food production by the end of the century – within our grandchildren’s lifetime.

3. The global social impact of climate change will not leave Estonia untouched

Inactivity does not mean that the current way of life can continue as before. Food and water security challenges are growing, affecting all countries through global economic crises, new pandemic outbreaks, violent conflicts over resource scarcity, and migration. It all affects Estonia both directly and indirectly. The fading hope of coping creates climate fears and reduces collective trust in politics. In such a world, the small countries’ prospects are certainly not the most secure.

Figure 2. Climate change attitudes among lower and higher income groups in Estonia and Europe (%). Source: Human Development Report 2023

4. The next decades will bring considerable changes not only in technology and the economy but also in the organisation of social life

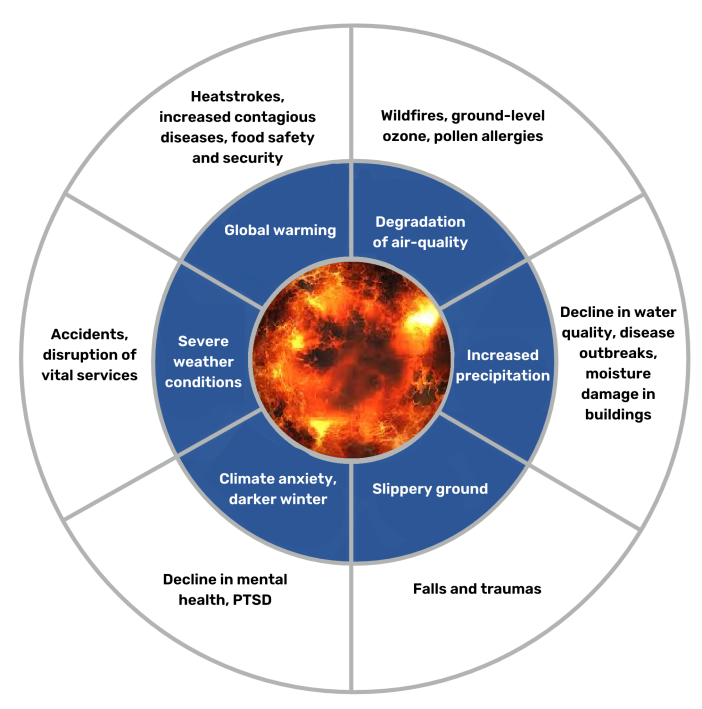

The impact of climate change on the health and well-being of the Estonian people will increase significantly by the end of the century. The nearly three-degree rise in average air temperature in Estonia has led to more intense heatwaves, but we lack the experience and social awareness to mitigate their effects. Storms and floods increase the risk of trauma. Droughty summers in Estonia and other regions are becoming more frequent, undermining food security. Increased ground-level ozone concentrations lead to poorer air quality, increase the risk of wildfires and make allergy-inducing pollen seasons longer and more intense. The latest IPCC synthesis report also highlights the mental health risks: all of the above-mentioned situations cause anxiety, stress and mental health problems.

5. Climate change has a direct health impact on the Estonian people

Public communication currently focuses on individual choices and their greening, as well as specific technologies (e.g. renewable energy) that distract attention from the need to take systemic action. To make the habits and practices of every individual and business more climate- and nature-friendly, including to produce and consume in a different way and less, to make things more durable and reparable, it is necessary to change the system: policymaking, legislation, market conditions, economic decisions, values and attitudes. It all cannot be controlled by a single lever. With the combined efforts of many actors, however, it is possible to guide it more or less in the desired direction, provided there is a sense of the bigger picture, an action plan and clear messages.

6. Nature conservation and restoration of degraded habitats are essential to mitigate the impact of climate change and maintain the natural environment

Nature is man’s most important ally. Climate change cannot be viewed separately from biodiversity loss and the destruction of the natural environment. According to a recent assessment of the Estonian red list of species (the so-called red data book), one in five species in Estonia is threatened with extinction. The area and connectivity of many important ecosystems – old forests, grasslands, low wetlands, etc. – are too limited to sustain their biota and natural benefits over the long term. Moreover, in recent years, land use in Estonia has aggravated climate change. Peat mines, drained wetlands, fields, settlements and intensively logged forest land now emit more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than the entire transport sector and waste combined.

Figure 3. Health impacts of climate change. Source: Hans Orru

7. Spatial planning and mobility are key issues; efforts made so far to reduce emissions and car congestion are insufficient

Estonia is one of the most car-intensive countries in the European Union (with 620 cars per 1,000 people in 2021). Since the 2000s, car commuting to work has increased. Household expenditure on transport has increased, as have the mileage of vehicles and greenhouse gas emissions from passenger cars (see also mobility statistics in Estonian compiled by the Transport Administration).

Urban areas are ever expanding – these are the paved street canyons with heavy traffic and little greenery, where air pollution, noise and heat stress are concentrated and where the mitigating effects of urban nature are absent. Such areas discourage physical activity and exacerbate car congestion. Urban heatwaves particularly affect poorer people, who are often older, in poorer health, without a second place to live, and with nowhere to hide from the heat and cool off.

8. Climate change and climate policy have a direct impact on our cultural and semantic space

The ever-proliferating climate and green vocabulary are like the EU jargon: people do not perceive the need to tackle the climate crisis as their own. We are lulling ourselves into believing that we love nature. At the same time, our everyday activities drive the climate and landscape changes, causing a shift in perceptions: we see the depleting natural environment and the changing living environment as normal and no longer ask for anything else. One of the consequences of the increased nature blindness, i.e. the inability to spot and recognise species and conditions characteristic of Estonian nature. This leads to the impoverishment of our perception and language. The Estonian word kuusik (spruce forest) can become as archaic as kedervars (yarn-spinning spindle). While a more efficient device has replaced the yarn spindle, there is no similar substitute for the living environment.

Nine urgent needs that should be addressed immediately

1. National climate service

Data on future climate conditions needs to be available in Estonia so that national and local planning can take account of the changing climate. Why erect structures and build transportation or energy systems that are not climate-resilient, or worse, that aggravate climate change? The Estonian government needs to ensure a national climate service providing current and future climate information.

2. Management of climate change mitigation and adaptation

To mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change, it is essential to create a nationwide management structure and share responsibility between national and local decision-making levels. This action must be based on the Climate Act. A forward-looking view is of utmost importance, and there is no time or space for climate- and nature-damaging decisions and investments. The decisions need to consider people’s different capacities and opportunities so that the change would not lead to more inequality (e.g. in access to housing renovation subsidies) but rather help people to come along with or suggest solutions themselves. Such a management structure requires new measurement and analysis systems adapted to the Estonian context and more inclusive governance practices (e.g. citizens’ conferences, and climate councils).

3. Crisis preparedness of local authorities and communities

People’s dependence on climate-sensitive infrastructure forces us to think about the alternatives that could be implemented in the event of prolonged power cuts caused by storms or other factors. Community preparedness involves both urban and rural flood and heatwave management plans and their discussion, as well as setting up and introducing early warning systems. Identifying society’s vulnerabilities enables people, communities and support systems, including providers of emergency, medical and psychosocial care, to know how to strengthen their preparedness. Everyone must make an effort to develop neighbourhood relations because more resilient communities support each other in crises and improve their self-reliance.

4. Moving towards smart spatial design

Spatial planning must not make people dependent on cars or allow housing development to expand into natural and agricultural areas. Fragmentation of the green network should also be avoided. Public transport must be functioning and accessible also outside densely populated urban areas. Spatial planning should prioritise pedestrian and cycling mobility, incl. creating a network of separate and uninterrupted cycle routes in cities. It is also important to avoid adding artificial pavements and to replace existing artificial surfaces with partially water-permeable and green areas, incl. with tall vegetation along streets, to provide shade from the blazing sun, among other things. Urban water bodies and flood buffering help cities to act as sponges, with the soil absorbing water and reducing flood risks.

5. Action plan for nature restoration and conservation

Estonia’s ecosystems need preserving, and damaged nature needs restoration so that the vital sources of clean food, water and air, recreation and culture would not get lost. Nature conservation should be the focus, and the principles of nature conservation must be represented in all sectors. First of all, effective protection of 30% of the land and 30% of the sea in Estonia must be ensured. A nature restoration plan must be prepared for Estonia to restore carbon sequestration from the land-use sector and to maintain biodiversity. That is in the interests of every citizen of Estonia.

6. Analysis of the health impacts of climate change

It is necessary to update the health impacts assessed in the Climate Change Adaptation Development Plan in 2015 and analyse to what extent the proposed adaptation measures have been implemented. A science-based forecast of health impacts gives a clear picture of the losses we are facing, so we can decide how to avoid them.

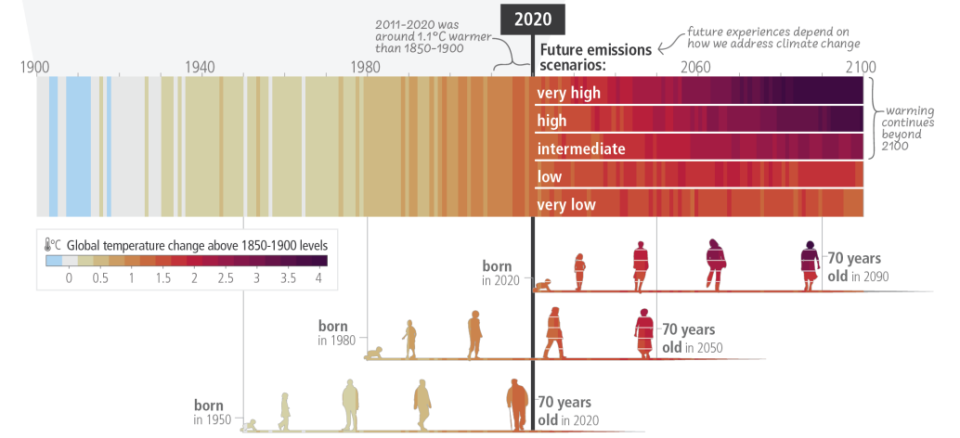

Figure 4. How the climate has changed and will change along the lifespan of three representative generations. Source: IPCC

7. Teaching the skills for shaping a sustainable future in the education system

The education system must teach professional green skills from general to vocational and higher education. For example, higher education institutions should know how to educate teachers who can teach students to repair things. It is also important for farmers to understand how to plan their work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Besides, it is necessary to spread the knowledge, skills and attitudes that help understand the inseparable link between human beings and nature and seek a balance between them. Sustainability issues are so diverse and all-embracing that it is necessary to educate teachers and lecturers, including teachers in disciplines who have so far thought that sustainability did not concern them. This is the only way to make the various societal changes resonate with each other.

8. The vocabulary of climate and green issues and language care

International studies have shown that a careful qualification of statements, characteristic of the scientific language, is knowingly used to spread climate scepticism. Decision-makers, therefore, need to formulate solid arguments and clear narratives to communicate the figures to each individual and point to the fact that change is in our backyard already. There are many crises, and the climate crisis does not seem clearly perceived in this context. However, a specific problem that is marked by a specific word will come across relatively better, be it drought or the effect of the disappearance of pollinating insects on our food supply.

9. Responsibility of the press in making sense of climate change issues

The Estonian press must interpret climate change and green transition as an existential issue that concerns everyone; and not as a political whirlwind, an impractical EU imposition, or even a niche topic for science or environmental enthusiasts. The media can highlight detailed experiences and lessons learned (including, treat pilot projects as a possible breakthrough for the future rather than an oddity), give a voice to those who have not yet had one, force slanderers to argue and enhance the mutual consultation of stakeholders. More demanding editing is needed when dealing with climate issues (including more effective fact-checking). In addition to the economic framework, we also need to speak of fairness, both in terms of the effect of the green transition on different social groups and the consequences of inactivity.

While, based on the above, the future looks rather grim, we still have a chance to avoid the worst. The IPCC synthesis report also recognises that the solutions implemented to reduce greenhouse gases in different countries have had an impact. Unfortunately, too little has been implemented, and the change has been too slow. Over the next decade, more vigorous action must be taken to make a decisive difference in mitigating future environmental change. In the context of Estonia, it is essential to recognise and learn to deal with the remaining bottlenecks in adapting to climate change. The number of options left for doing so is shrinking every year. This is why we need to make crucial decisions now while there is still time because we can only adapt to the crisis later. We are doing that for the health and well-being of ourselves, our children and the future of our country.

Authors: Margit Keller, Aveliina Helm, Velle Toll, Raili Marling, Piia Post, Age Poom, Hans Orru, Kati Orru, Triin Vihalemm, Maie Kiisel